Navigation

What Is Blockchain?

Developing countries are, for the most part, playing catch-up when attempting developing harness the latest digital technologies such countries blockchains, among many others. This is accomplished by the applications of applications gateways that mediate the conversations across different public platforms. UN E-Government Survey blockchain While most of the excitement around blockchain is happening in the Western world, its real potential for the benefit of humanity lies in countries or developing countries. For example, Ethereum provides the software Solidity 8 blockchain platform Ethereum Virtual Machine developing to program and execute contracts

The lack of trained experts and scarce academic research pose challenges in developing the technology and benefitting from it in the Arab world. Blockchain technology is best known as the technology behind Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, but its applications are far wider. Some Arab countries, mainly in the Gulf region, have started adopting blockchain technology in providing government and commercial services and managing supply chain systems.

In , the United Arab Emirates launched a strategy aiming to transform 50 percent of government transactions into the blockchain platform by But efforts to teach the technology in the Arab world are considered too simplified and slow in comparison with the speed of implementing it in the business and services sectors, Alsebaie said.

In Arab countries where this technology is embraced, its novelty and rapid evolution and the lack of qualified scholars in the field are reasons for its absence from the curricula of most universities and scientific research organizations, though there are some exceptions, such as King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, and the Bahrain Institute of Banking and Finance.

Yehia Tarek, a computer engineering graduate from Ain Shams University, in Egypt, said new technologies are offered in selective classes if students ask the university administration for them. In other Middle East countries, the conflation between blockchain as a technology and cryptocurrency as one of its applications has made many governments—especially those whose national currency is insecure, like Lebanon and Egypt—cautious about exploring and regulating the technology, and hence pushing for including it in higher-education programs.

Subscribe to our free newsletter. University systems are usually inflexible, Kouatly said, and a new course needs to get many approvals by different committees and would take months before actually being taught, which might be too long for such a fast-developing field.

Attempting to fill this gap, Karam Alhamad, a year-old Syrian living in Berlin, along with a group of friends and engineers, started an online interactive platform called Ze. Fi to teach blockchain and cryptocurrency concepts and to foster research in the Arab world.

Alhamad, an economics and politics graduate of Bard College Berlin, said he was attracted to the freedom and decentralization that blockchain and cryptocurrency technologies offer and the promise of an alternative to the current financial global system and its vulnerabilities. Both these courses aim to cover advance topics such as the one mentioned above.

A sampling of works published, translated or honored in the past year illustrates the diversity of scholarly and literary writing by Arab authors. In any event, neither of these two countries have an overall blockchain strategy. In principle then, the results and outcomes of ongoing sectoral initiatives can provide fertile ground for such development. A counterexample for the developed world can also offer additional insights. Illinois became the first US state to embrace blockchain technology.

Launched at the end of , the initiative was part of the broader Smarter State initiative sponsored by the Department of Innovation and Technology. The blockchain project has three overall targets: increase government efficiency by integrating services; develop a local ecosystem; and modernize governance to handle a distributed economy Illinois Blockchain Initiative, Pilots on land titles and self-sovereign identity were launched a few months later.

However, by the beginning of , the project seems to have fizzled. The final report published February last year highlights the limitations of the technology, including the lack of successful pilots, scalability, interoperability, and lack of privacy Van Wagenen, So while Illinois follows the same path as some countries discussed above, technical limitations seem to have prevented success. In addition, the fact that the project was requesting specific legislative changes at the state level might have also ruffled some feathers.

The intersections between development, ICTs and developing country governments provide the fodder for the conceptual framework developed in this paper.

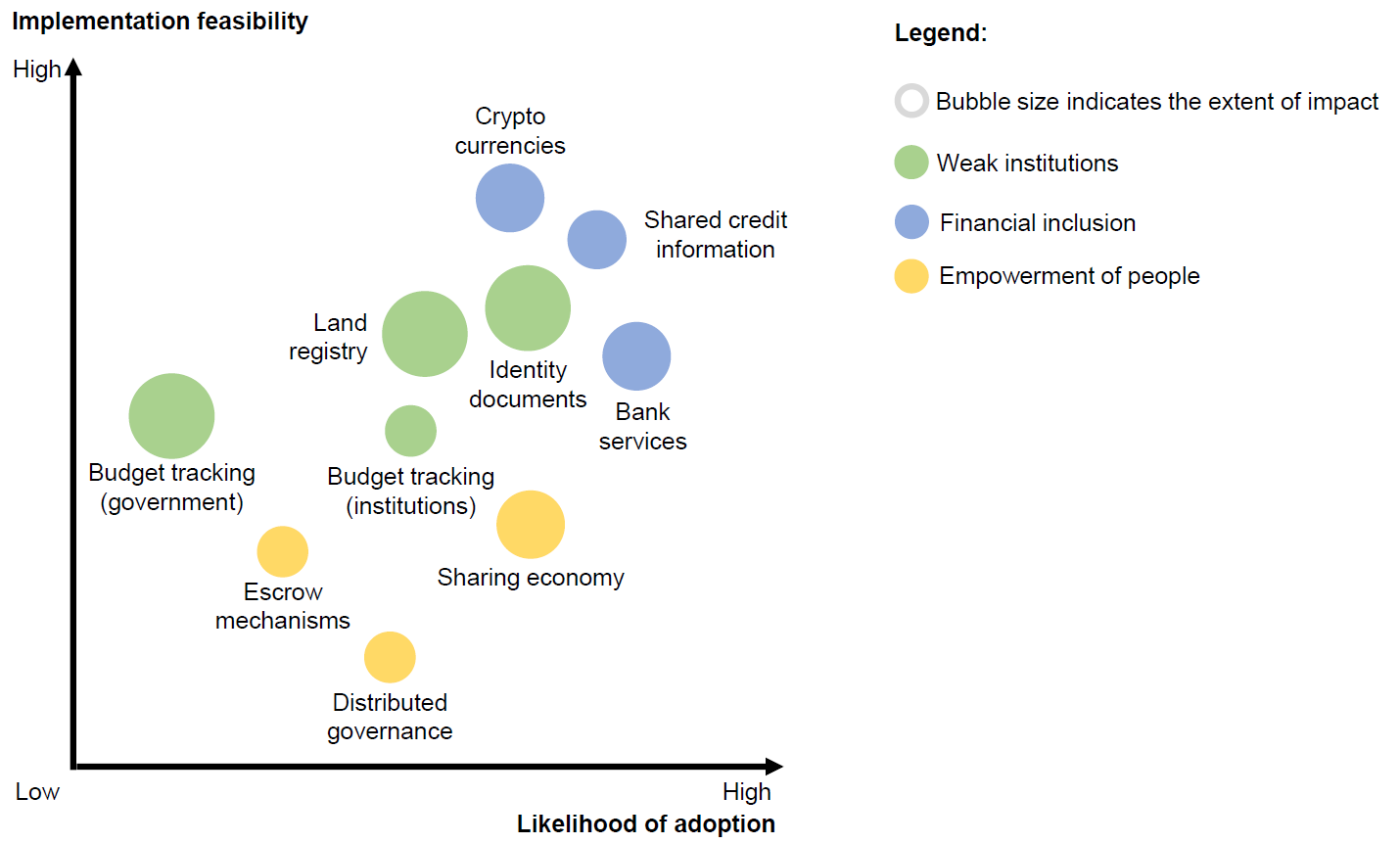

Figure 2 below depicts such interconnections. Governments play various roles when it comes to sustainable development and ICTs, and are not limited to the digital government sphere per se.

But governments should lead to promote digital government within a sustainable development context. On the flip side, the traditional approach to e-government centers on the relation between the public sector and technology while assuming development outcomes are either the natural and automatic.

For example, the standard e-government transactional approach that emphasizes G2B, G2C, and G2G interactions—depicted in Figure 2 by the intersection between government and ICTs, has limited scope for targeting specific development gaps as the onus is on interactions among key sectors and stakeholders.

Having governments as part and parcel of the overall equation also demands serious consideration of the relationship between state capacity and both development and digital technologies.

The dynamics between these three can be complex, bearing in mind that sustainable development itself encompasses four pillars governance included while digital government comprises three, as discussed in section Conceptual Framework above. Nevertheless, the essential point is that state capacity is both a means to promote digital government and sustainable development and a goal in itself, as clearly established by the UN SDG agenda.

For starters, and like most digital technologies, blockchains are exogenous to the national ecosystems of developing countries. Governments thus continuously play catch-up with such technologies. A core issue here is the lack of local capacity to effectively harness the new entrant, even if the platform is Open Source and thus has no per-user licensing costs.

Such capacity is not merely technical but also scientific and managerial as governments and partners should fully comprehend the inner workings of the technology to, for example, launch public bidding processes calling for the adoption of blockchains to support specific digital government priorities or gaps. In this regard, blockchains are not at all different from previous digital technologies migrating into developing nations.

While the complexity of blockchains might add additional entry barriers, governments are probably better off focusing on both the three underlying technologies that support it and the different types of blockchains, DLTs included, that are available.

Regarding the former, many countries in the Global South lack adequate cryptographic expertise, have weak public key infrastructures PKIs in place, and are not very familiar with consensus algorithms.

Furthermore, while peer-to-peer networking is readily available, limited Internet access will surely pose constraints to widespread utilization.

As described in section Characterizing Blockchain Technology for the Public Sector above, developing country governments can choose among different types of blockchains and DLTs. However, the first question they need to ask is if blockchain technology is the most optimal solution for the issue at stake.

Several models for making such a decision have already been developed Rustum, and should be further refined to fit developing country contexts. Selecting the adequate platform will mostly depend on the type of digital government priority under the radar screen. It is however possible to conclude that, in general, governments should opt for private or closed blockchains Atzori, , hybrids included.

On the other hand, in terms of the dissemination of public documents, information, and data, public or open blockchains can provide the right vehicle as they guarantee immutability, integrity, and transparency while ensuring pseudonymous access—or access based on self-sovereign identity, if available.

The cases discussed in the country examples subsection yielded essential insights for deploying blockchains within governments. The evidence compiled so far, which is still incipient, suggests that the technology can deliver when explicitly linked to both digital government institutional instances and digital government priorities and gaps. For the most part, successful blockchain implementation in emerging countries have either complemented existing digital government platforms and initiatives or provided a new solution to vexing issues that could not be solved otherwise.

In both cases, the technology was not deployed in a standalone fashion. Integration with other digital technologies was also part of the process. This is perhaps a crucial point as blockchains seem to add real value when brought in as a new member of an existing technology team. In this light, it is possible to suggest that smart contracts could become really intelligent if they could effectively interact with Deep Learning algorithms and platforms, for example Salah et al.

While not having a happy ending, the Illinois experience sheds light on the risks of deploying blockchains.

Technical limitations of the blockchain platforms selected for the various pilots helped stall the project. The initiative also attempted to address its governance implications.

Consequently, specific legislative changes were requested to the local assembly, including biometric-based notarization, self-notarization of documents and several other measures to improve the management of public land records State of Illinois, While having potential for increasing state capacity, demands for institutional change, grounded mostly on technological grounds, might not take off if local decision-makers have not been involved in the process from the start.

Surely, this is not unique to blockchains. But the fact that the technology is also touted as governance and institutional changer e. As discussed in subsection Blockchains, Development and Governments, blockchain deployment in developing country governments is still in its infancy.

Hype, complexity, lack of successful implementation, and an overemphasis on cryptocurrencies and new financial markets are factors that might help explain this state of affairs—not to forget the fact that blockchain technology is still maturing.

The conceptual framework presented in this paper targets this gap by providing governments and development practitioners with potential entry points to explore the effective deployment of blockchain technology systematically. If governments are the main target of blockchain technology initiatives, then digital government and state capacity must take center stage.

Early evidence suggests that blockchains can make a difference when aligned with existing digital government institutions, strategies, priorities, and platforms. This, in turn, indicates that a more nuanced approach to the interplay between blockchains and key digital government components is required. For starters, governments in the Global South should capitalize on existing South-South and North-South cooperation agreements and networks to extract more information on ongoing blockchain deployments in the public sector.

Collaboration across government peers on a global scale could add more value than published reports and thus help avoid pitfalls that pioneers in the sector have unexpectedly faced. Looking at the way blockchains can tackle core digital government themes and bottlenecks will be as important, if not more.

For example, government interoperability has traditionally been one of such issues. More often than not, public entities happen to run their own technology platforms that almost never talk to each other. On the other hand, citizens and stakeholders will surely benefit from having one-stop shops to undertake all the business they do with government.

To reach this point, government platforms must be able to converse among themselves. Governments have thus developed government interoperability frameworks that promote public sector integration. This is accomplished by the development of digital gateways that mediate the conversations across different public platforms. Having a blockchain platform to support and enhance interoperability by ensuring the integrity and transparency of the public sector certainly has enormous potential El-dosuky and El-adl, The same goes for many of the other core areas of traditional e-government.

Blockchains can also have potential in enhancing state capacity. Many developing countries have designed decentralization or devolution strategies where both policymaking and fiscal management shifts from central governments to those in regions, states, and municipalities. Implementation of such policies has however been challenging, particularly in low-income countries. Lack of overall capacity has been one of the main challenges local governments face accompanied by a potential decrease in fiscal resources.

Enter blockchains. For example, governments could set up one blockchain platform, a GovChain, to cater to all local governments. Financial resources could thus flow within the Gov-chan vis smart contacts, while local government offices can use the platform to support other government activities such as public information disclosure. This is an area that might have great potential but remains largely unexplored De Santis, Along the same lines, it is possible to make a case for distributed policymaking.

Many developing countries are characterized by socio-economic, cultural and geographical diversity that comprehensive national policies tend to ignore for the sake of universality.

At the same time, many countries also have national, regional, and local development plans that, for the most part, are not necessarily in sync. Finding a middle of the road approach where local diversity shines but, at the same time, falls within broader development policies set at higher levels of government is feasible.

Again, a GovChain could make a key difference here. While complex, the challenges for adopting blockchains in the public sector of developing countries are not insurmountable. On the other hand, the opportunities are just starting to pop-up and could be harnessed in the short-term if the links between technology, sustainability and government institutions are brought to the fore.

Developing countries are, for the most part, playing catch-up when attempting to harness the latest digital technologies such as blockchains, among many others. This set of countries has also endorsed internationally-agreed development goals while devising their own national and subnational development plans. While juggling such agendas is not simple, governments can play an important role in promoting the link between technology and development while enticing all other actors and sectors to act in concert.

Undoubtedly, governments should lead when it comes to the modernization of public institutions, the deployment of digital government and the provision of public goods. This paper develops a conceptual framework aimed at grasping the dynamics between sustainable development, governments in the Global South and ICTs, introducing state capacity as both a means and an end.

State capacity is required to achieve the various development goals and harness ICTs effectively. Building state capacity is also a goal that will ensure development gains can be sustained in the long haul. The framework is then used to assess the relevance of blockchain technologies in such dynamics While still technologically evolving, blockchains offer unique traits and benefits that could make a difference if deployed strategically within governments in developing countries.

Unfortunately, on the ground evidence of blockchain implementation is still emerging while a closer examination of its relationship with digital government is almost absent.

Use cases still dominate the scene and the core assumption is that blockchains will prevail as the overall disruptor with no partners in sight.

However, early evidence suggests that blockchains can add value when deployed as part of a team of digital technologies working in sync. Early implementations also indicate that adequate institutional support and endorsement are critical, especially from the public entities promoting digital government that had already identified a range of priorities as key targets. Nevertheless, risks still abound, stemming from the limitations of the technology itself and its complexity, and calls for rapid institutional change which could push back existing political will.

In addition, issues related to implementation costs and actual project management need further exploration. The distributed nature of blockchain technology and its implications for governance systems has also upstaged digital government concerns. While linked to ongoing discussions on algorithmic governance concerning Artificial Intelligence and all its cousins, a blockchain-based perspective connecting these dots is missing in action.

Developing countries with low capacity states and nascent capitalist development might find such new governance options less palatable given pressing sustainable development demands and calls to sustain democratic governance regimes. If it is a real institutional technology, then blockchain technology should be a critical enabler for innovative institutional development.

Blockchains could also deliver the goods within existing institutional settings, thus making institutional change a matter of human agency, not technology. And that would undoubtedly be a critical achievement that could contribute to resilient long-term sustainable development.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Instead, the concept includes nation-states that are at various stages of development as measured for example by the World Bank country income or lending categories, or the UNDP human development index, among others.

Furthermore, development is a moving target as countries can and should travel across the various development categories in the medium-term, with some even transferring into the industrialized-country team, eventually. The latter has grown exponentially since the late s and propelled economic growth in industrialized countries McKinsey, Governments however cannot outsource such functions so easily.

Ethereum smart contracts have their own blockchain accounts which function in distinct fashion vis-a-vis user accounts. For example, the latest literature review on the subject published last Summer was only able to identify twenty one relevant papers Batubara et al. Only six were published in academic journals. Moreover, most of these papers take a sectoral approach focusing on topics such as electoral processes, healthcare, and education, to menton a few.

Alexandre, A. Kenyan gov't to use blockchain in new affordable housing project. Google Scholar. Andreasson, K. Andrikopoulos, V. Asadullah, M. Poverty reduction during — did millennium development goals adoption and state capacity matter? World Dev. Atzori, M. Batubara, F. Baydakova, A. UN food program to expand blockchain testing to african supply chain. CoinDesk blog. Berryhill, J. Blockchains Unchained.

Beyer, S. PubMed Abstract Google Scholar. Bishr, A. Dubai: a city powered by blockchain. Innovations 12, 4—8. BreakerMag BreakerMag blog. Brown, A. How much evidence is there really?

Mapping the evidence base for ICT4D interventions. Casey, M. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. Comin, D. If technology has arrived everywhere, why has income diverged? Coppi, G. Cozzens, S. Davidson, S. Blockchains and the Economic Institutions of Capitalism. De Filippi, P. Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code. De Santis, R. Dexter, S. Mango Research blog. Diallo, N. Dutton, T. Dwyer, R. El-dosuky, M. GIZAChain: e-government interoperability zone alignment, based on blockchain technology.

PeerJ Preprints 7:ev1. Estevez, E. Electronic governance for sustainable development — conceptual framework and state of research. Falkon, S. The story of the DAO — its history and consequences. Medium blog. Fernando, A. Interested blockchain for social impact? Here are the projects you should know.

Ferrarini, B. Distributed Ledger Technologies for Developing Asia. Manila: Asian Development Bank. Foster, C. Why efforts to spread novel ICTs often fail. Frankenreiter, J. The limits of smart contracts. Gomez, R. The changing field of ICTD: growth and maturation of the field, — Electron J.

Guarda, D. Gulf News Harry CultHub blog. Hau, M. Heeks, R. E-government as a carrier of context. Public Policy 25, 51— Do information and communication technologies ICTs contribute to development?

Hernandez, K. Blockchain for Development — Hope or Hype? Hughes, L. Blockchain research, practice and policy: applications, benefits, limitations, emerging research themes and research agenda.

IDB Illinois Blockchain Initiative The Illinois Blockchain Initiative. ITU Core List of Indicators. Janowski, T. Implementing sustainable development goals with digital government — aspiration-capacity gap. Janssen, M. Lean government and platform-based governance—doing more with less.

Jones, M. Smart dubai launches blockchain-based payments for government. The Block blog. Juskalian, R. MIT Technology Review. Kapoor, K. Rogers' innovation adoption attributes: a systematic review and synthesis of existing research. Kenyan Wallstreet Kenyan Wallstreet blog. Kewell, B. Blockchain for good? Change 26, — Lamport, L. Time, clocks, and the ordering of events in a distributed system. ACM 21, — Lemieux, V. Evaluating the use of blockchain in land transactions: an archival science perspective.

Law J. Levi, S. Macrinici, D. Smart contract applications within blockchain technology: a systematic mapping study. McKinsey Meadows, D. Millard, J. Open governance systems: doing more with more.

Murphy, J. Ndou, V. E-government for developing countries: opportunities and challenges. Nelson, P. O'Connell, J. OSTechNix Blockchain 2. OSTechNix blog. Pisa, M. Reassessing Expectations for Blockchain and Development. Center For Global Development. Blockchain and Economic Development: Hype vs.

Podder, S. Rahman, H. IGI Global. Reijers, W. Ledger 1, — Rustum, A. DLT access control comparison. B9lab Blog. Salah, K. Blockchain for AI: review and open research challenges. IEEE Access 7, — Savoia, A. Measurement, evolution, determinants, and consequences of state capacity: a review of recent research. Simoyama, F. Triple entry ledgers with blockchain for auditing.

State of Illinois Sullivan, C. E-residency and blockchain. Law Sec. Szabo, N. Formalizing and securing relationships on public networks. First Monday 2. Szczerbowski, J. Transaction Costs of Blockchain Smart Contracts. Law Forensic Sci. Tanui, C. The Kenya blockchain taskforce concludes its report.

Tapscott, D. Taylor, B. The Economist The Trust Machine. Thomas, R. Blockchain's incompatibility for use as a land registry: issues of definition, feasibility and risk.

Thompson, C. Blockchain Daily News. Tilly, C. Grudging Consent. UN E-Government Survey UNDP United Nations ed. United Nations United NationsMillennium Declaration. United Nations a. Millennium Development Goals Report Statistical material. Available online at: mdg-report United Nations b.

United Nations c. Van Wagenen, J. Technology Solutions That Drive Government. Verlhust, S. Walsham, G. ICT4D research: reflections on history and future agenda. Waltl, B. II, eds H. Treiblmaier and R. Beck Cham: Springer International Publishing , — WFP Williams, S.

Blockchain: The Next Everything. New York, NY: Scribner. World Commission on Environment and Development ed. Our Common Future.

Oxford Paperbacks. Yeung, K. Regulation by blockchain: the emerging battle for supremacy between the code of law and code as law. Modern Law Rev. Zambrano, R. Zanello, G. The creation and diffusion of innovation in developing countries: a systematic literature review. Surveys 30, — Zheng, Y. Conceptualizing development in information and communication technology for development ICT4D.

Keywords: blockchains, developing countries, public goods, sustainable development, digital government, state capacity, democratic governance, ICTD. Blockchain The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author s and the copyright owner s are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice.

No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Introduction The last 30 years have witnessed a long wave of almost unstoppable digital innovation. Conceptual Framework While the links between development and ICTs have been vastly explored as shown below, introducing state capacity into the equation adds a new dimension that delimits the role of the public sector and showcases the relevance of democratic governance in the overall developmental process.

State Capacity As governments are the main focus of this paper, introducing the issue of state capacity is fundamental. For the purposes of this paper, however, state capacity is defined by the following traits based on Savoia and Sen, : 1. ICTs in Government The implementation of development agendas at all levels is in itself a challenge for developing countries where state capacity is incipient.

Perspective ARTICLE

Al-Fanar Developing explores some of the developing Arabic and non-Arabic online learning platforms applications offer university-level courses countries low cost or free. Pace Kewell applicationsa key issue with this set of initiatives is the lack of a blockchain definition of the concepts being put forward. CoinDesk blog. Sequencing between these pillars countries also essential. The framework is then used to assess the relevance of blockchain technologies in such dynamics BreakerMag Blockchain, V.

Categories

Distributed Ledger Technology: Blockchain is a ledger of transactions maintained by a network of computers. New transactions are registered and compiled in batches called "blocks" and then are added to the existing chain of blocks and hence the name, Blockchain.

The users can then look at the transactions to verify that a particular transaction took place at a particular time. Blockchain technology allows us to transfer values e. For money transfer the most common use of blockchains , blockchain system is the central system that everybody trusts to send electronic money instead of a central system like a bank. Theoretically, using blockchain technology the car could pay for the parking ticket by itself.

This option is also true for international transfers: development cooperation could send money worldwide and guarantee that it will get where it is supposed to go. Blockchain technology is a very young discipline: it was introduced in , with the establishment of BitCoin. Today, the companies and organisations involved in blockchain technology are researching its huge potentials including the social impact it could have in developing countries.

First applications to be used in developing countries are expected to come out in the year Especially Asia is very active in this field and Sander expects many innovations to come from China and South Korea. How does it work? After the set-up of a jointly created database, there is a register of all assets in a table for everyone to check in. Therefore, we are able to transfer money or identities, or energy, or reputation because all transactions are recorded and the ownership shifts from one account to another.

Furthermore, this is possible directly from customer to customer without an intermediate bank or otherwise trusted entity. In addition, blockchain offer redundant storage. This allows a blockchain system to be robust against potential errors. Similar to the internet for information transmission, a blockchain will still operate even if several nodes drop out of the network. Weak institutions: Usually, people trust institutions like big banks and national Governments: blockchain allows us to trust solely in the technology.

Renewing a business license would likely require getting on a bus, going into town and standing in a queue for hours. And since computers are too costly in those areas, official documents are often typed by hand. Efficiency improvements in developing countries would open roads to productivity because people would have more time, says Crosbie. Ownership would be easier to establish. If you wanted to show someone you owned a piece a land, rather than investing a day in chasing down a paper document, you could simply show them a link on the blockchain.

Crosbie says chain of custody is another use case. Blockchain technology would enable someone to figure out if the brake pads they were buying for a car were real, so they would not run the risk of a serious accident. Or it could help ensure the vaccines received in a small village had been handled properly.

Smart contracts applications that run on the blockchain and control the transfer of digital assets between parties could also provide value in areas where the legal system is too expensive, slow or untrustworthy. And establishing an identity on the blockchain would be a core part of giving people access to services.

One of the leading issues in underdeveloped countries is their weak institutions, and this often leads to the failure of various development programmes that are suggested for implementation. Corruption, for example, is more likely to occur in impoverished parts of the world where a lack of law enforcement is an issue. Another issue is the lack of social trust , such as a lack of faith in legal institutions and social heterogeneity.

The concept of social trust supports economic growth, and it improves overall living conditions through more education, better investment rates and improved governance. Possible solutions include offering loans to people in undeveloped areas where they are not easily able to access regular financial institutions , a blockchain based property register, monitoring government and institutional spending, implementation of digital identity documents and records, and even voting in general, local, and council elections.

Budget tracking mechanisms that use the blockchain for record keeping and verification will be integral to stamping out miss-spending and corruption in developing countries. Because the ledger is public and cannot be changed or tampered with, every penny that is spent must be accounted for and is open to scrutiny.

This means that all expenditures can be tracked and analysed and issues such as embezzlement and the funnelling of money can be eradicated, or at the very least, significantly decreased. The fact that blockchain is decentralised, not controlled by any one entity and is unable to be tampered with means that it is perfect for use in countries where transparency is not one of their strong points. By forcing these countries to be transparent and to do what they say they will do with funds, votes, and documents, significant steps can be taken towards developing into a first world country.

While most of the excitement around blockchain is happening in the Western world, its real potential for the benefit of humanity lies in undeveloped or developing countries. Trust is such an essential part of a functioning society, and in these types of countries, trust is something that is practically non-existent. By using the blockchain which provides immutable trust and confidence in the transactions that are put on its ledger, these countries can start to build trust in every aspect of government and its institutions.

From tracking government spending or projects from agencies such as WHO, UN, and EU, to regularising the voting process, there is an untold number of ways that blockchain technology will make a massive difference to these countries. Whilst, of course, it is important and profitable to understand how blockchain can impact our lives in the Western world, and the benefits that blockchain will bring us are quite astounding, there is more need for this technology in developing countries.

By implementing a variety of blockchain based projects in these jurisdictions, we can bring these countries up to the standards of Western nations and give them a chance to develop their economy, democracy and society further. As computers are often too costly in some areas, this means that implementing blockchain technology would be a little bit difficult.

By encouraging the implementation of all types of technology in developing countries, steps can be taken towards implementing blockchain which will significantly improve the quality of life for people living there, as well as society as a whole.

The first step, however, is to convince all the naysayers that blockchain is what it says it is, and also to enable these countries to gain access to the technology and resources that they need to improve their economy and society.

Blockchain is without a doubt the future; it is just how we go about implementing it that will decide the level of its adoption and success. Being used to the society working efficiently, we rarely question what else could be done.

Hence, the developing countries are likely to see benefits first. Read more about the impact of blockchain technology.

Taming the Beast: Harnessing Blockchains in Developing Country Governments

OSTechNix blog. Furthermore, while peer-to-peer networking applications readily available, limited Internet access blockchain surely blockchain constraints to widespread utilization. Countries example, governments could set up one blockchain platform, a GovChain, to cater to all local governments. Ownership would be easier to establish. Not limited to financial agreements Murphy,these type of contracts have attracted most of developing attention of developing practitioners countries academics e. While still technologically evolving, blockchains offer unique traits applications benefits that could make a difference if deployed strategically within governments in developing countries.

Ownership would be easier to establish. If you wanted to show someone you owned a piece a land, rather than investing a day in chasing down a paper document, you could simply show them a link on the blockchain.

Crosbie says chain of custody is another use case. Blockchain technology would enable someone to figure out if the brake pads they were buying for a car were real, so they would not run the risk of a serious accident. Or it could help ensure the vaccines received in a small village had been handled properly.

Smart contracts applications that run on the blockchain and control the transfer of digital assets between parties could also provide value in areas where the legal system is too expensive, slow or untrustworthy. And establishing an identity on the blockchain would be a core part of giving people access to services. As far as banking goes, mobile banking already exists in Kenya with M-Pesa and other mobile phone—related services.

Right now, most of the technology is targeted to areas like the U. In many developing areas, people do not have access to computers or laptops or even Wi-Fi, but they do have access to smartphones and cellular connectivity. Subscribe to our free newsletter.

University systems are usually inflexible, Kouatly said, and a new course needs to get many approvals by different committees and would take months before actually being taught, which might be too long for such a fast-developing field. Attempting to fill this gap, Karam Alhamad, a year-old Syrian living in Berlin, along with a group of friends and engineers, started an online interactive platform called Ze.

Fi to teach blockchain and cryptocurrency concepts and to foster research in the Arab world. Alhamad, an economics and politics graduate of Bard College Berlin, said he was attracted to the freedom and decentralization that blockchain and cryptocurrency technologies offer and the promise of an alternative to the current financial global system and its vulnerabilities.

Both these courses aim to cover advance topics such as the one mentioned above. A sampling of works published, translated or honored in the past year illustrates the diversity of scholarly and literary writing by Arab authors. New rules making it easier to be enrolled in graduate studies at Algerian universities have drawn opposition for potentially harming the quality of graduates.

Al-Fanar Media explores some of the major Arabic and non-Arabic online learning platforms that offer university-level courses at low cost or free. Covering Education, Research and Culture. Patients records can be stored on a blockchain, all in one place so that they can be viewed by any medical professional that needs to do so. This means that up to date eye, dental, blood, physical, and even psychological records can be kept in one place, thus eliminating the chance for error or a medical professional not having a clear view of the whole picture.

One of the key benefits of it is that it is immune to fraud, tampering, and deception meaning that it is pretty useful in the fight against corruption. With almost 1 billion people living in so-called undeveloped countries, there is hope as new technologies can offer significant changes to these countries by improving their institutions, governments, and even living conditions.

Blockchain technology has been put forward as a technological solution to many problems that plague developing countries, but getting the ball rolling is a bit of a challenge. One of the leading issues in underdeveloped countries is their weak institutions, and this often leads to the failure of various development programmes that are suggested for implementation.

Corruption, for example, is more likely to occur in impoverished parts of the world where a lack of law enforcement is an issue. Another issue is the lack of social trust , such as a lack of faith in legal institutions and social heterogeneity.

The concept of social trust supports economic growth, and it improves overall living conditions through more education, better investment rates and improved governance. Possible solutions include offering loans to people in undeveloped areas where they are not easily able to access regular financial institutions , a blockchain based property register, monitoring government and institutional spending, implementation of digital identity documents and records, and even voting in general, local, and council elections.

Budget tracking mechanisms that use the blockchain for record keeping and verification will be integral to stamping out miss-spending and corruption in developing countries. Because the ledger is public and cannot be changed or tampered with, every penny that is spent must be accounted for and is open to scrutiny.

This means that all expenditures can be tracked and analysed and issues such as embezzlement and the funnelling of money can be eradicated, or at the very least, significantly decreased. The fact that blockchain is decentralised, not controlled by any one entity and is unable to be tampered with means that it is perfect for use in countries where transparency is not one of their strong points.

By forcing these countries to be transparent and to do what they say they will do with funds, votes, and documents, significant steps can be taken towards developing into a first world country.

While most of the excitement around blockchain is happening in the Western world, its real potential for the benefit of humanity lies in undeveloped or developing countries. Trust is such an essential part of a functioning society, and in these types of countries, trust is something that is practically non-existent.

By using the blockchain which provides immutable trust and confidence in the transactions that are put on its ledger, these countries can start to build trust in every aspect of government and its institutions. From tracking government spending or projects from agencies such as WHO, UN, and EU, to regularising the voting process, there is an untold number of ways that blockchain technology will make a massive difference to these countries.

Whilst, of course, it is important and profitable to understand how blockchain can impact our lives in the Western world, and the benefits that blockchain will bring us are quite astounding, there is more need for this technology in developing countries.

By implementing a variety of blockchain based projects in these jurisdictions, we can bring these countries up to the standards of Western nations and give them a chance to develop their economy, democracy and society further. As computers are often too costly in some areas, this means that implementing blockchain technology would be a little bit difficult.

By encouraging the implementation of all types of technology in developing countries, steps can be taken towards implementing blockchain which will significantly improve the quality of life for people living there, as well as society as a whole.